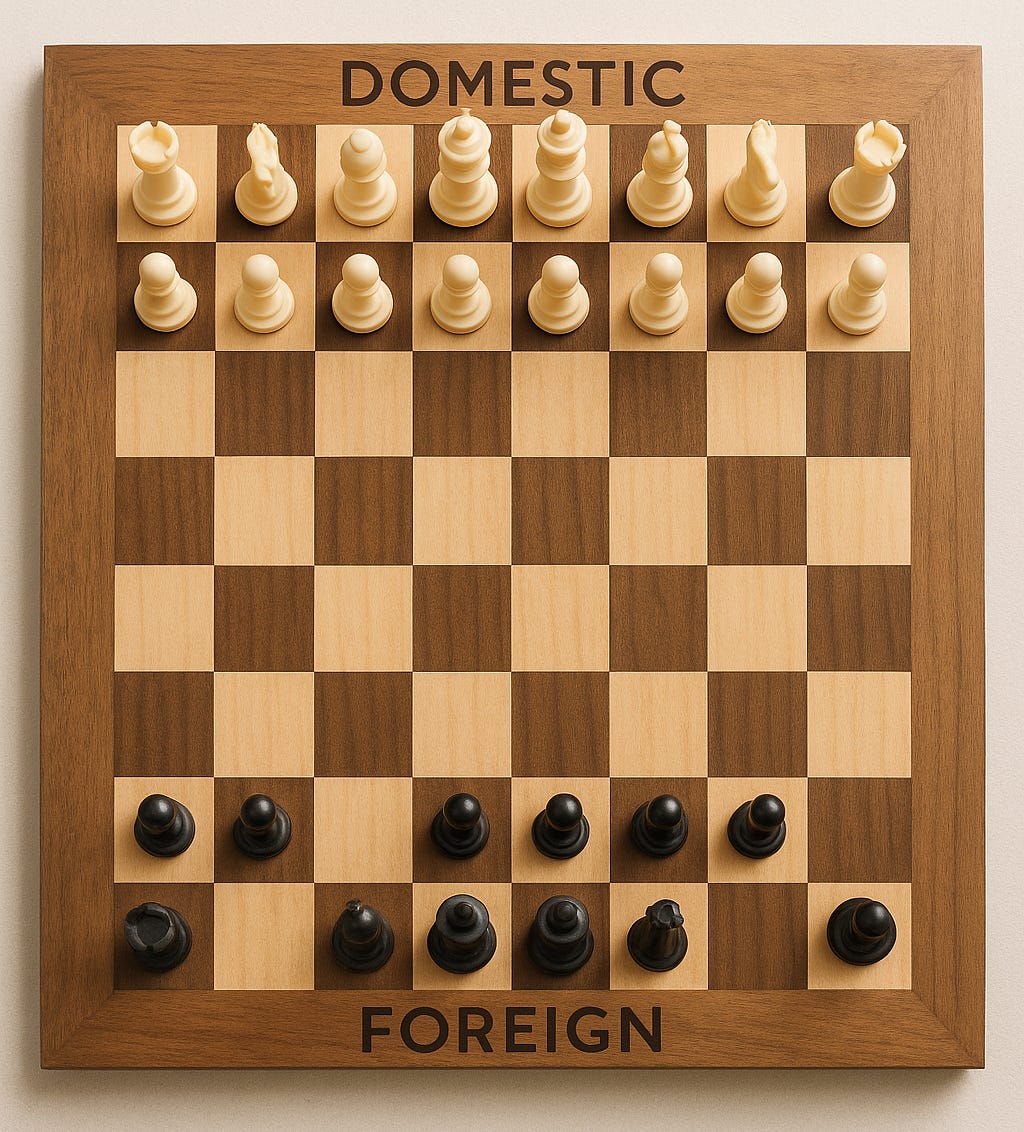

National Treatment: Principle or Practice?

Inside the national-treatment debate: theory, evidence, and the line between bias, burden, and selection.

National treatment requires that foreign applicants receive the same legal treatment as domestic applicants. This principle is embedded in Article 2 of the 1883 Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property and is reaffirmed under the 1995 TRIPS Agreement. The national treatment principle is a cornerstone of international patent law and binds the vast majority, if not all, of the world’s patent systems. Yet, despite its prevalence today, national treatment has not always been the norm. The U.S. Patent Act of 1836 set application fees of $30 for national applicants, $500 for any “subject of the King of Great Britain,” and $300 for all other persons.

Why discriminating?

Economists have studied governments’ incentives to treat foreign patentees less favorably than domestic ones. A core reason for discrimination is that governments seek to maximize national welfare rather than global welfare. A welfare-maximizing government cares about domestic producers’ profits and consumer surplus but not foreign profits [1]. Weaker protection for foreigners can raise national welfare by facilitating imitation and faster diffusion of imported technologies. In this view, stronger protection for a foreign company looks like a transfer abroad with limited domestic upside.

Difei Geng and Kamal Saggi show that trade frictions strengthen this logic [2, 3]. With tariffs, transport costs, or other wedges, export-market protection is less valuable to firms than home-market protection. If national treatment forces a single level of protection for locals and foreigners, it prevents governments from tailoring policy to those wedges and can depress innovation incentives.

Yasukazu Ichino notes another efficiency argument, related to optimal discretion. Governments would optimally give stronger protection to the firms that are more responsive to it and weaker protection to the firms that are less responsive. Requiring national treatment forces the government to provide uniform protection, thereby reducing global welfare under certain conditions.

Finally, beyond pure welfare calculus, states face strategic motives. Discrimination can operate as industrial policy—tilting the field toward domestic R&D, encouraging leapfrogging in “strategic” sectors, or selectively weakening foreign rights where local absorptive capacity is low [4].

Is there a case for not discriminating?

Discrimination is often justified as industrial policy, but the effect on domestic R&D is not uniformly positive. Reiko Aoki and Thomas Prusa show that the impact of discrimination hinges on the industrial context. In infant industries, favoring the domestic firms can raise their efforts, yet in mature industries with lucrative incumbent products, protection induces a replacement effect—current rents dull incentives to invest in the next generation. In short, the same lever that can accelerate catch-up in nascent sectors can entrench complacency where established innovative products already earn rents.

The welfare calculus also flips once we relax the frictions that motivate discrimination. Whereas Geng and Saggi show that trade wedges make asymmetric protection appealing, in low-friction or liberalized trade settings, the authors show that national treatment can raise world welfare by increasing the value of foreign markets and reducing the static consumer cost of foreign patent rights.

Strategic considerations cut both ways. Just as discrimination can serve industrial policy, open favoritism invites retaliation—tit-for-tat fees, enforcement hurdles, or litigation strategies—that may dissipate any short-run domestic gains. National treatment also advances fairness and legal parity, thereby lowering political risk premia for multinational R&D.

Finally, national treatment addresses the global failure arising from governments maximizing their own country’s welfare. It acts as a coordination device: by committing to non-discrimination, countries reduce the scope for beggar-thy-neighbor policies, raise the expected value of foreign markets ex ante, and shift private incentives toward socially efficient (global) R&D.

The many facets of discrimination

We could be forgiven for thinking that discrimination belongs to the past. On paper, it mostly does: de jure discrimination—rules that openly treat foreigners differently—has largely disappeared. For instance, Tajikistan maintained distinct fee bases for foreigners until it adhered to the national treatment principle in 2011, in line with WTO standards [5]. But in light of rising trade tensions and talk of “technology protectionism,” this issue is emerging in the empirical literature.

Outcome gaps can persist de facto. Even with identical rules on paper, foreigners may face heavier effective burdens. Sometimes, the mechanism is intentional but operates through discretion rather than statute. For example, governments can pursue “second-degree” discrimination by quietly tightening practice in government-designated strategic sectors while keeping the statute facially neutral. At other times, the mechanism is unintentional, driven, for instance, by language barriers or procedures.

Discrimination in the patent prosecution process has been measured along two margins. At the extensive margin, scholars have asked whether a right is obtained at all; at the intensive margins, they have asked how costly, how slow, and how narrow that right becomes.

A rich literature documenting differences in outcome

Early cross-office comparisons reported systematic differences by applicant residence. Masaaki Kotabe showed that the Japan Patent Office (JPO) appears to discriminate against foreign applicants with longer pendency periods than for domestic applicants. In contrast, Western patent offices appear to discriminate against foreign applicants with lower patent grant rates than for domestic applicants.

Outcomes in China have been subject to the most scrutiny. Overall, the literature finds that Chinese applicants receive grants faster than foreigners, and the bias is largest in strategic fields [4, 6, 7]. The picture concerning grant rates is mixed. While some analyses found bias against foreigners in grants, others found that aggregate grant rates were higher for foreigners due to better-quality patents compared to locals [4, 6, 8, 9].

The literature on post-grant outcomes is considerably thinner, but the existing empirical findings present a mixed picture of home-country bias. In Canada, Joseph Mai and Andrey Stoyanov found that foreign firms are about 25 percentage points less likely to prevail in court when asserting IP. In China, Christian Helmers and colleagues found that foreign companies perform as well, if not better, than local firms in patent suits. Furthermore, foreign patentees received remedies commensurate with those given to domestic patentees. However, the remedies during the study period were extremely low—probably too low to act as an effective deterrent.

Differences in outcome do not “prove” discrimination

Differences in outcome do not, by themselves, suffice to establish discrimination. Many reasons could explain discrepancies in grant lag or grant rates between foreigners and locals. For instance, foreigners may take longer to respond to the patent office’s communications, thereby increasing grant lags. Regarding the grant probability, there may be intrinsic differences in the quality of inventions between foreigners and locals. Correlation is not causation, and establishing the causal impact of being a foreigner on the outcome of the patent prosecution process is key to affirming discrimination.

The economic literature offers many studies of discrimination. Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan have proposed a rather neat way of establishing discrimination in the labor market. They sent fictitious resumes to help-wanted ads in U.S. newspapers. To manipulate the perceived race of the job applicant, the authors randomly assigned resumes to African-American- or White-sounding names. They found that White names received 50 percent more callbacks for interviews.

Adopting such an approach to studying discrimination in the patent system is, however, not feasible. One cannot just send the same fictitious patent applications several times, but simply changing the applicant’s origin; patent applications are only granted to inventions that are new to the world, and duplicate inventions would be quickly spotted and rejected on the grounds of novelty.

Elizabeth Webster and colleagues have proposed a clever test of discrimination. They have used a matched sample of patent applications granted by the USPTO and filed at the JPO and the European Patent Office (EPO). In other words, they observe patent applications for the same invention in three jurisdictions (so-called ‘twin patents’). They found that Japanese firms were less likely than European firms to have their patent applications granted in Europe (and vice versa at the JPO). Because this method compares the fate of the same inventions across different jurisdictions, it alleviates concerns about systematic differences in the quality of inventions by foreigners and locals. A follow-on study using more recent data and a larger number of patent offices found similar results.

However, this method has its limits. Although it compares the same invention by the same applicant in different jurisdictions, the applicant may behave differently across jurisdictions. For example, it may hire more qualified patent attorneys in its domestic market or know best how to navigate the intricacies of its national patent system.

The story does not end here

To address these concerns, empirical research has recently delved into the details of the examination process. Bruno van Pottelsberghe and colleagues have tracked several metrics related to the intensity of the examination process performed by patent examiners at the USPTO, EPO, and JPO. They confirm that international applicants face a lower grant probability than locals. However, when analyzing the underlying internal processes, researchers found no convincing evidence of discrimination. This leads to the conclusion that the disparity in grant outcomes is likely driven by economic forces or heterogeneous applicant behavior, such as a reduced willingness or capacity of applicants to invest time and resources to maintain their patent application active “at all costs” in foreign jurisdictions.

Some work with a former student of mine focused precisely on this question, seeking to measure the applicant’s level of effort at the USPTO. Our model included the number of final and non-final rejections received, as well as the total count of transactions initiated by the applicant during the prosecution phase. A higher count of rejections or a greater number of applicant transactions was taken as evidence of greater effort by the assignee, reflecting higher costs and a greater willingness to fight for the patent. These transaction data revealed that foreigners generated fewer rejections and fewer examiner and applicant transactions than locals, consistently suggesting that they put less effort into the prosecution process. In other words, the lower grant rates and greater scope reductions for foreigners are partly explained by the fact that they concede more or abandon earlier than domestic applicants.

A clear case of discrimination?

Together with Emilio Raiteri, we have exploited the twin-patent approach within a statistical framework that allows controlling for a large number of variables that could affect the grant rate, such as the “quality” of the patent attorney firm. Interestingly, as we start controlling for more and more variables, traces of foreign discrimination in China vanish. They vanish for all but one type of patent application: those in technological areas the Chinese government considers strategic. We also find that these applications are subject to more amendments during the examination phase.

In a follow-up study, joined by Rudi Bekkers, we provide additional evidence of strategic discrimination against foreign innovators in China. We utilized a novel identification strategy leveraging standard-essential patents (SEPs): we tracked whether foreign SEP applications were publicly disclosed as essential to a standard (such as 3G/4G mobile communication standards) before or after substantive examination began. We find that foreign SEPs declared as such before examination took place were approximately nine percentage points less likely to be granted in China than those disclosed after substantive examination. Furthermore, these early-disclosed foreign applications faced a one-year prosecution delay and experienced greater scope reduction than later-disclosed applications.

Looking forward

The emerging picture is nuanced. Outcome differences between foreign and local applicants are real in many settings, but they do not by themselves establish discrimination; composition and behavior matter, and credible identification requires designs that hold constant invention quality and other “unobservables.” Where stronger designs exist, evidence of systematic bias often weakens, yet targeted disadvantages can remain—especially in government-prioritized fields or when procedural frictions (such as translation and timeliness) bite unevenly.

Collectively, these studies have only scratched the surface of the discriminatory treatment of foreigners. We need to dig more into the data to understand the root causes of the apparent discrimination. Scholars have proposed new statistical methods and examined various stages of the patent prosecution process. We need more such methods (or ‘identification strategies’ in economists’ jargon) and more metrics to identify the channels through which discrimination might occur. Finally, the literature has focused primarily on the largest offices because they provide high-quality data. But the more opaque offices might also be those discriminating the most, calling for more scrutiny.

If you enjoy evidence-based takes on patents and innovation, join hundreds of readers who receive The Patentist directly in their inbox.

Please cite this post as follows:

de Rassenfosse, G. (2025). National Treatment: Principle or Practice? The Patentist Living Literature Review 9: 1–6. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.5702262.

Hi, a very interesting read. Just want to clarify when you say "foreign" essentially the focus is patents by non-residents. What about the foreign firms' affiliate filling as residents? Is there any evidence to support that these affiliates are also discriminated against? Thanks, ruchi