When standards meet patents: The economics of SEPs and FRAND (Part I)

Standards create enormous economic value by making products work together. But they also create a special kind of bargaining over patents.

A small museum could be built from the world’s electrical plugs: three prongs, two prongs, angled pins… and the adapter industry that exists only because standards differ. The punchline is that none of these designs is intrinsically “better” in a technological sense. They are better in the only sense that matters once coordination happens: they match what everyone else uses. When a society converges on a plug type, that choice quietly dictates what appliances can be sold, what adapters get bought, and how expensive it is to switch later.

That is the economics of standards in miniature. A standard is a shared specification that makes independent components work together. When it succeeds, it creates network effects (compatibility becomes more valuable as adoption grows) and reduces transaction costs (fewer tests, less customization, and fewer negotiations). But it also creates lock-in: once the ecosystem coordinates, deviating from the standard becomes costly, even if an alternative looks superior on paper. Standards, therefore, deliver large efficiency gains—and they also redistribute bargaining power toward whoever controls the critical interfaces.

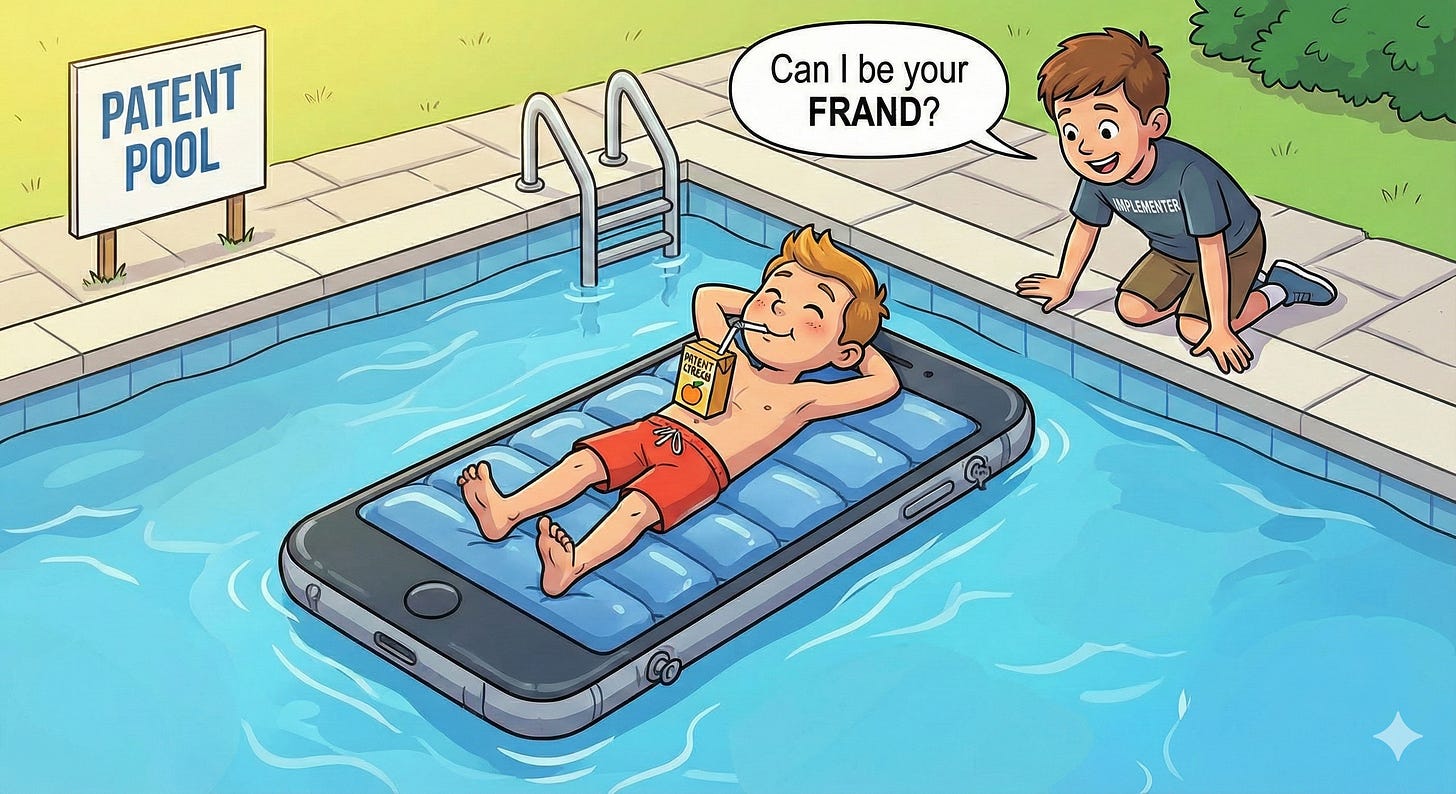

Now replace plugs with technical standards (Wi-Fi, 5G, video codecs) and replace interfaces with patents. In many industries, implementing a standard requires the use of specific patented technologies. Those patents become standard-essential, and the same coordination that makes standards valuable can turn licensing into a high-stakes bargaining problem. That is the entry point for a jargon-heavy literature: SEPs, FRAND, patent thickets, and patent pools. The article delves into this rich and complex topic, covering the institutional plumbing that keeps interoperability from turning into gridlock. The argument unfolds in four steps: why standards coordinate markets; why SEPs transform bargaining; how FRAND and pools try to manage the resulting frictions; and why noisy essentiality claims complicate everything. Part I addresses the first two topics, and Part II covers the last two.

Standards and SSOs: coordination with rules

As the opening example illustrates, a compatibility standard is a shared specification that enables products and services to interoperate. Its economic value is often less about the intrinsic technical merit of a particular design and more about the fact that many independent actors agree to build to the same interface. In markets with strong network effects, such as the telecommunications industry, that agreement can be decisive: the value of a product rises as more users adopt compatible versions and more complementary products plug into the same ecosystem.

As Joseph Farrell and Garth Saloner explain, standardization can solve a basic coordination problem. Without a focal point, industries may face excess inertia—firms delay adoption while waiting to see what others will do—or costly standards wars, where incompatible technologies split the market and force duplication of effort. By converging on a common interface, standards reduce transaction costs, support economies of scale, and make it easier for innovators to build compatible complements.

Standard-setting organizations (SSOs), such as ETSI or 3GPP, are one way industries create that focal point. They provide a process for developing, selecting, and maintaining standards—effectively turning a coordination problem into a governed, repeatable procedure. Crucially, once standards become widely adopted, the interface they define can become economically powerful: it shapes what can be sold, what must be compatible, and how costly it is to deviate later.

Interestingly, the issue of excess inertia may also occur once a standard exists, if a new, superior alternative becomes available. Farrell and Saloner also analyze whether the benefits of standardization can “trap” an industry in an obsolete or inferior standard when a superior alternative is available. They find that when there is incomplete information regarding firms’ preferences for one standard over another, “excess inertia” can occur, causing an industry to fail to adopt a new standard even when doing so would benefit all parties. This inertia arises because firms act as “fencesitters,” willing to join a “bandwagon” once it begins but unwilling to be the first to switch, for fear of being stranded with an incompatible technology if others do not follow.

From standards to patents: what makes a patent “essential”?

Once a standard is adopted, “compatibility” ceases to be a preference and becomes a requirement: products must implement the specified interface to participate in the ecosystem. This is where patents enter the story. A standard-essential patent (SEP) is a patent that must be used to comply with a standard. In the strict technical sense, it is not possible to implement the standard without infringing the patent.

Essentiality matters because it changes the market structure of licensing. Before standardization, technologies can compete: multiple approaches may perform the same function, and implementers can select among substitutes. After standardization, that competitive constraint largely disappears. If a patented technology is baked into the standard, implementers cannot “design around” it while remaining compliant. In economic terms, standardization can produce what Nobel Prize winner Oliver Williamson calls a “fundamental transformation”: an environment with alternatives ex-ante becomes one with no effective substitutes ex-post.

Two additional features amplify this shift. First, Carl Shapiro notes that essential patents are perfect complements: to implement the standard legally, an implementer may need licenses from many SEP holders. If the standard requires N separate essential patents, holding N−1 licenses is not “almost compliant”—the product still infringes. Second, essentiality is often not a clear, court-validated label. In many SSOs, patents are self-declared as potentially essential, and declarations are rarely verified. Because SSOs do not verify essentiality claims, and because firms can face significant legal and contractual consequences for failing to disclose relevant patents, firms have an incentive to declare more patents than necessary.[1]

Put these pieces together, and the bargaining environment looks very different from ordinary patent licensing. Joseph Farrell and colleagues frame standard setting as shifting bargaining from ex-ante competition to ex-post leverage. They explain that implementers make sunk, standard-specific investments (engineering, testing, certification, supply chains). Once those investments are made and the market coordinates on the standard, SEP holders can gain bargaining leverage they did not necessarily have beforehand. This is the economic backdrop for the two recurring disputes in SEP licensing: hold-up and hold-out. A hold-up occurs when SEP owners try to charge for the value created by lock-in rather than for the ex-ante incremental value of the invention. After an implementer has sunk millions into designing a smartphone or a car to comply with 5G, switching away from the standard if the patent holder demands a high royalty is rarely a realistic option—creating lock-in. A hold-out occurs when implementers strategically delay taking a license, relying on enforcement frictions and limits on remedies.

From the patent holder’s perspective, essentiality also shifts enforcement economics: once a standard is widely adopted and the patented technology is unavoidable, potential infringement can be widespread and costly to police across many implementers. FRAND commitments can therefore be seen not only as a constraint on leverage, but also as a mechanism that facilitates broad licensing and more predictable compensation.

At this point, the puzzle is clear: the very coordination that makes standards valuable can also hand SEP holders (and, in a different way, implementers) bargaining leverage that has little to do with the invention’s intrinsic merit. So what can standard setters do—without becoming price regulators—to keep licensing in a neutral zone? Part 2 covers the core responses: FRAND as an ex-ante commitment, why injunction leverage matters, and how thickets, stacking, and pools complicate the picture.

If you enjoy evidence-based takes on patents and innovation, join hundreds of readers who receive The Patentist directly in their inbox.

Please cite this post as follows:

de Rassenfosse, G. (2026). When standards meet patents: The economics of SEPs and FRAND. The Patentist Living Literature Review 11: 1–11. DOI: TBC.

The electrical plug example is perfect. Nothing says "we figured out lock-in economics" like needing a drawer full of adaptors just to charge your phone in differnet countries. Atleast patents don't require literal baggage.

Really solid breakdown of how lock-in transforms bargaining dynamics. The Williamson framing about the ex-ante to ex-post shift is key here. Had a situation a while back where we had to license tech built intostandards and the negotiation felt way more constrained than typical patent deals. What's interesting is that this power imbalance could've been way worse without FRAND commitmens from the start.